Circular Economy and Me – Issue 14

Chemicals are everywhere in our lives. Whether a natural or synthetic product, they are all made of chemicals. As such, chemical manufacturing is a vast, global enterprise. In the UK alone, the chemical industry had an annual turnover of £32 billion, corresponding to 1% of GDP and creating 99,000 direct jobs in 2019. It is one of the UK’s largest export sectors and demand is predicted to at least double in the next 10 years. It is a hugely significant pillar of the UK economy.

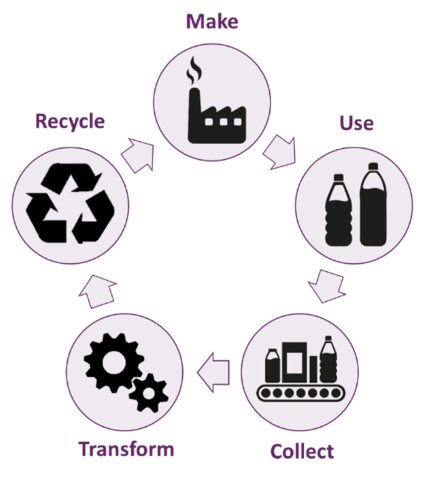

However, this scale comes at an environmental cost. It is heavily energy- and resource-intensive, creating vast quantities of waste and greenhouse gas emissions. This is due primarily to our global linear economies of take-make-use-dispose. Resources are extracted, turned into products, used by consumers and then largely disposed of. At each stage of this economy, there is waste and high use of energy which all accumulates into a large polluting footprint.

A Circular Economy (CE) offers a vision where products and materials are designed to be reused, repaired or remanufactured, ensuring resource extraction, waste generation and pollution are kept to a minimum. For the chemicals sector, this will largely involve re-using typical “waste” streams as valuable commodity feedstocks, such as CO2.

In my role within CircularChem, I am looking at the broader policy implications and requirements to drive towards a circular transition, of which finance plays a significant role. This is a capital-intensive industry – manufacturing infrastructure, energy use and resources are all significant costs and oftentimes barriers to start-ups entering the market.

Recently, we have held a series of workshops with senior representatives from academia, industry and financial institutions to discuss the perceived policy blockers and enablers, key emerging or established technologies that will help and the financial and fiscal requirements needed to enable a circular transition. These have proved extremely fruitful and we are planning a final workshop later in the year to brief MPs and policymakers on our key recommendations.

There was collective agreement that greater collaboration is needed between academia, industry, financial institutions and government. Only together can real change be made. Additionally, it was highlighted that the UK is not seen as an attractive place to invest in novel technologies owing to high labour and manufacturing costs and risk-aversion amongst investors.

We are ensuring that all of our policy recommendations are evidence-based, which is not always the case with some current policies. We designed our workshops to be led by our participants, particularly industry representatives, so we could better understand their needs, wants and obstacles to be overcome. These have been extremely fruitful discussions and have shown a great desire and ambition for change. A bold step in the right direction is needed.

For further information related to this research, the following references may be useful:

- Newman AJK, Dowson GRM, Platt EG, Handford-Styring HJ and Styring P (2023), Custodians of carbon: creating a circular carbon economy. Front. Energy Res. 11:1124072. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2023.1124072

- Lamb KJ and Styring P (2022), Perspectives for the circular chemical economy post COP26. Front. Energy Res. 10:1079010. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.1079010

Written by Thomas Franklin, centre research associate.